How metaphors frame our understanding of COVID-19

“Nous sommes en guerre [We’re at war]”, declared French President Emmanuel Macron on 16th March 2020. He wasn’t declaring war against another country but against COVID-19. The virus had become a pandemic, and its global impact was known in less than 3 months.

Our understanding of COVID-19 often involves metaphors. Their use helps to frame a topic because metaphors emphasize or deemphasize certain information. The framing can shape the way we think about a topic. For example, the phrase ‘the world’s a stage’ is metaphorical. It starts a monologue from Shakespeare’s As You Like It, where a character compares life with a play. Like a play, in life, men and women are ‘players’ with ‘parts’, and with ‘exits’ and ‘entrances’.

COVID-19 has generated various metaphors although war metaphors dominate the conversation, as noted by the media in France, Spain, the United Kingdom and the United States. War metaphors are similarly encountered in Indonesia, Singapore and Malaysia. In Indonesia, President Joko Widodo invited G20 leaders to fight a war. For him, Indonesians can fight the onslaught because they’re a nation of fighters. The President makes world leaders and Indonesians ‘soldiers’ against the virus.

In Singapore, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong reminds Singaporeans to ‘keep our guard’ and to ‘keep families safe…and Singapore secure’. Mr. Lee says ‘the world is in an intensifying battle, and the battle will be long’. Singapore later decided to implement stricter movement controls. Mr. Lee advises fellow citizens to ‘batten down to fight’ and to join healthcare workers on ‘the frontline’. His metaphors imply an escalation of the reaction. Citizens need to be directly involved because he uses a word with military origin in relation to the virus, ‘frontline’.

In Malaysia, Prime Minister Muhyiddin Yassin also utilizes war metaphors. Malaysia combats the virus because it threatens the lives of citizens. Mr. Muhyiddin recognizes Malaysia is ‘at war with invisible forces’ but the burden is mostly placed on healthcare workers who ‘battle’ the virus. COVID-19 is a serious cause for concern and everyone should have some responsibility in ‘the war’.

We’ve looked at political leaders because their powerful position ensures their ideas are spread, and their position often means many people would trust them. Leaders influence our perception of COVID-19, and can increase or decrease panic. Besides politicians, the media influences our perception. War metaphors are common, as in the headline ‘Perang belum berakhir [The war is not over]’. The sense of conflict is taken for granted, and it inspires related metaphors. For instance, the United States is a ‘lanun moden [modern pirate]’ who diverts face mask supplies.

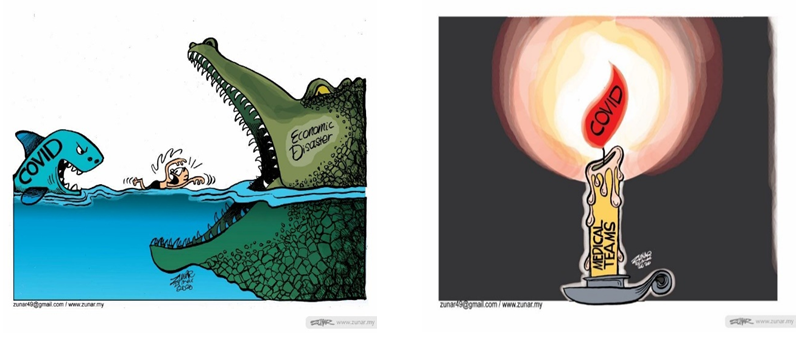

Metaphors are utilized in language and can also be utilized in image. Look at Zunar’s cartoons below. COVID-19 is a threat because it is visualized as a shark with sharp teeth and a flame, about to consume citizens and healthcare workers. In political and media discourses, the virus is dangerous, and we need to confront it before it destroys us.

You may ask, “So what?” Metaphors entail meanings, and the choice of metaphors can shape our activities. If COVID-19 is a war, then we may react like in any other war. War and other metaphors of danger identify a threat and its severity. These metaphors justify government monopoly of actions and decisions. They remove personal or social autonomy, which is replaced by government-led order. The government is managing the virus, and citizens must contribute. War metaphors presume unity, where everyone fights together. Group behavior is encouraged, making it virtuous to donate resources, such as food, masks and money.

But war is optional, unlike this deadly virus. For survival, we have no choice besides resolving COVID-19. War metaphors create heroes and enemies. Healthcare workers and others are named ’frontliners’, the heroes fighting COVID-19. Some question this naming because their sacrifice becomes the focus. It obscures the shortage of equipment and drugs. It also marginalizes most of us, who are part of the solution. Typical enemies are external but the virus is inside the human body. Treatment must simultaneously harm one and heal the other.

War metaphors are divisive, and can strengthen ethnic, national or regional prejudice and discrimination. Residents of Wuhan and Hubei, people of Chinese ethnicity or nationality, and Asians have reported cases of xenophobia although the virus can target any human being. Moreover, war metaphors justify draconian reactions, and our democratic systems and practices may be put on hold. Rights for people and the environment may be ignored or relaxed in order to solve COVID-19. Any government must maintain accountability during this crisis, although we may be told the contrary.

COVID-19 was previously named the novel coronavirus but the metaphors to refer to it are not novel. Many diseases, such as AIDS, Ebola, SARS, Zika, avian flu and swine flu are described and explained using metaphors. War metaphors are only one way to think about diseases. The linguists Veronika Koller, Inés Olza, Elena Semino and others are advocating for alternative and better metaphors. A creative public has produced metaphors of journey, music, sport, and vehicle. For example, ‘we need to work as a team’, ‘the match with COVID-19 continues’, or as the Director General of the WHO writes, ‘You can't win a football game only by defending. You have to attack as well’.

Metaphors are critical to thinking about COVID-19. A holistic choice of metaphors can inspire solidarity, care, and physical and mental strength. Metaphors should emphasize our shared humanity because the pandemic does not know boundaries. We’re not at war. Instead, we need to manage and ultimately cure this deadly virus. As we do so, we also need to #reframecovid.

Thanks to the students of HEA 101 Semester II 2019/2020 for their feedback on the draft!